A Contradictory Ruling on Copyright

And why BARTZ, not KADRY, will win out over time

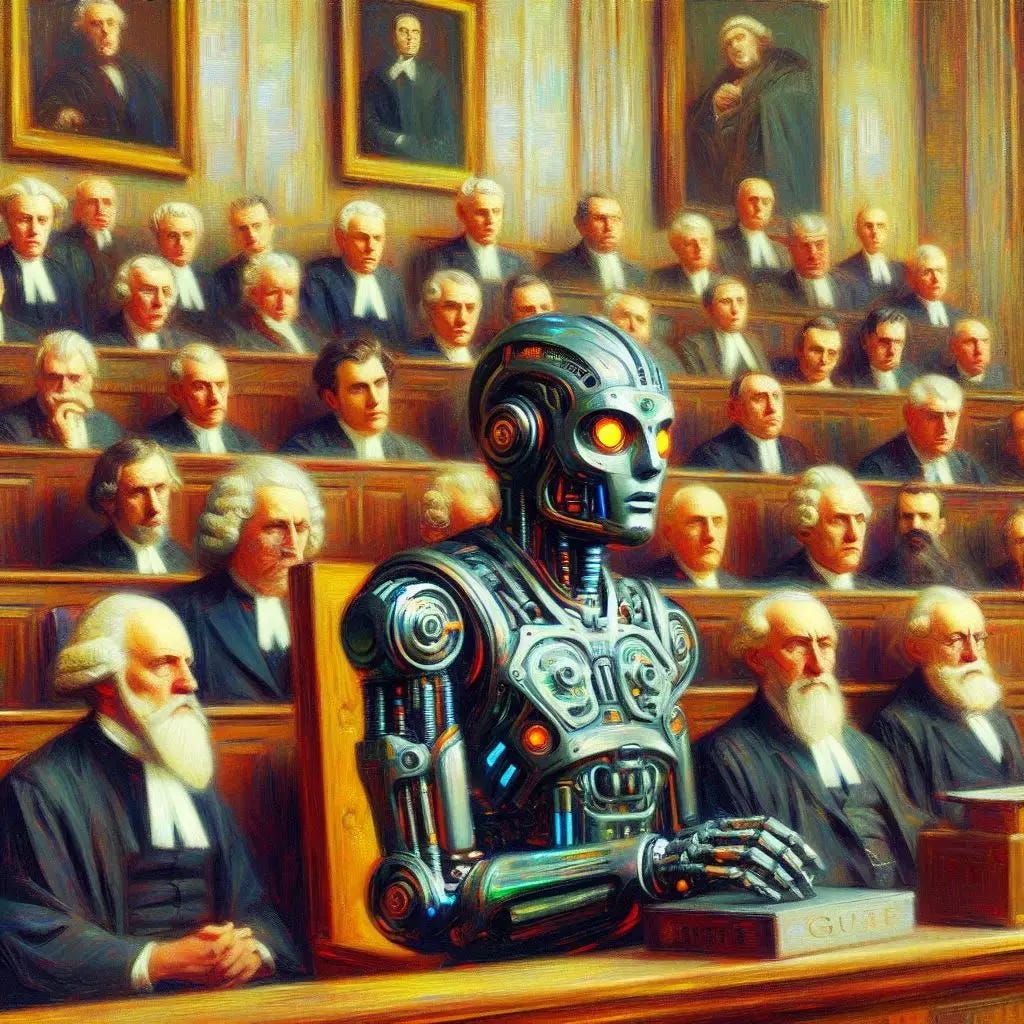

A second decision, by a different court in a different case, Kadry v Meta, has contradicted the recent ruling in the Bartz v Anthropic case that determined AI training is protected by the fair use doctrine and does not violate copyright. However, a comparison of the two decisions make it clear that it is the Bartz interpretation that will dictate the ultimate outcome.

Kadrey is another suit by authors against the developer of an AI model, in this case Meta’s ‘Llama’ chatbot. The authors in Kadrey asked the court to rule that fair use did not apply.

Much of the Kadrey ruling by Judge Vince Chhabria is dicta—meaning, the opinion spends many paragraphs on what it thinks could justify ruling in favor of the author plaintiffs, if only they had managed to present different facts (rather than pure speculation). The court then rules in Meta’s favor because the plaintiffs only offered speculation.

But it makes a number of errors along the way to the right outcome. At the top, the ruling broadly proclaims that training AI without buying a license to use each and every piece of copyrighted training material will be “illegal” in “most cases.” The court asserted that fair use usually won’t apply to AI training uses even though training is a “highly transformative” process, because of hypothetical “market dilution” scenarios where competition from AI-generated works could reduce the value of the books used to train the AI model..

That theory, in turn, depends on three mistaken premises. First, that the most important factor for determining fair use is whether the use might cause market harm. That’s not correct. Since its seminal 1994 opinion in Cambell v Acuff-Rose, the Supreme Court has been very clear that no single factor controls the fair use analysis.

Second, that an AI developer would typically seek to train a model entirely on a certain type of work, and then use that model to generate new works in the exact same genre, which would then compete with the works on which it was trained, such that the market for the original works is harmed. As the Kadrey ruling notes, there was no evidence that Llama was intended to to, or does, anything like that, nor will most LLMs for the exact reasons discussed in Bartz.

Third, as a matter of law, copyright doesn't prevent “market dilution” unless the new works are otherwise infringing. In fact, the whole purpose of copyright is to be an engine for new expression. If that new expression competes with existing works, that’s a feature, not a bug.

As I pointed out in a recent Darkstream, the only reason authors are resorting to copyright law is because it’s all they have, even though their real objective is to prevent AI from successfully imitating and improving upon their literary styles. This was a point that did not escape the judge in the Bartz case.

Importantly, Bartz rejected the copyright holders’ attempts to claim that any model capable of generating new written material that might compete with existing works by emulating their “sweeping themes, “substantive points,” or “grammar, composition, and style” was an infringement machine. As the court rightly recognized, building gen-AI models that create new works is beyond “anything that any copyright owner rightly could expect to control.”

Let’s face it, most AI-generated works are considerably less derivative than all the high fantasy novels that have been published ever since Terry Brooks first imitated Tolkien in The Sword of Shannara.

China’s AI models are being trained on vast corpora, including (illegally scraped) English-language works the U.S. refuses to free for domestic use.

The result? U.S. copyright law is helping foreign adversaries build better American-language AIs than American citizens are legally allowed to.

On my blog ( https://offmodernity.substack.com/ ), I've written so far two novels, "The Sorter" and "The Null Shard", with each consisting of three parts. I also released them on Amazon for Kindle.

"The Sorter" was first written out in the traditional manner, then edited and stripped down using Grok, then fleshed out with better dialogue and descriptions using Claude. It was inspired by Vox Day and the SSH, although that is only one element; the emphasis is on an alien invasion of a future American space colony on an alien planet.

"The Null Shard," which takes place immediately following, after writing out the first few chapters traditionally, was then organized and outlined with the help of Grok, then with rough drafts using Grok, and then fleshed out using Claude. At all steps, of course, I myself had to do a lot of adding, editing, and correcting of the outputted material to keep it consistent between chapters and with the overall storyline.

These two works are my first-ever forays into science fiction writing.